This month’s blogathon feature is David Lynch, the director most responsible for showing me film’s unlimited potential. It was a near conversion experience for me when I saw Blue Velvet so long ago, and I revere his dreamscapes.

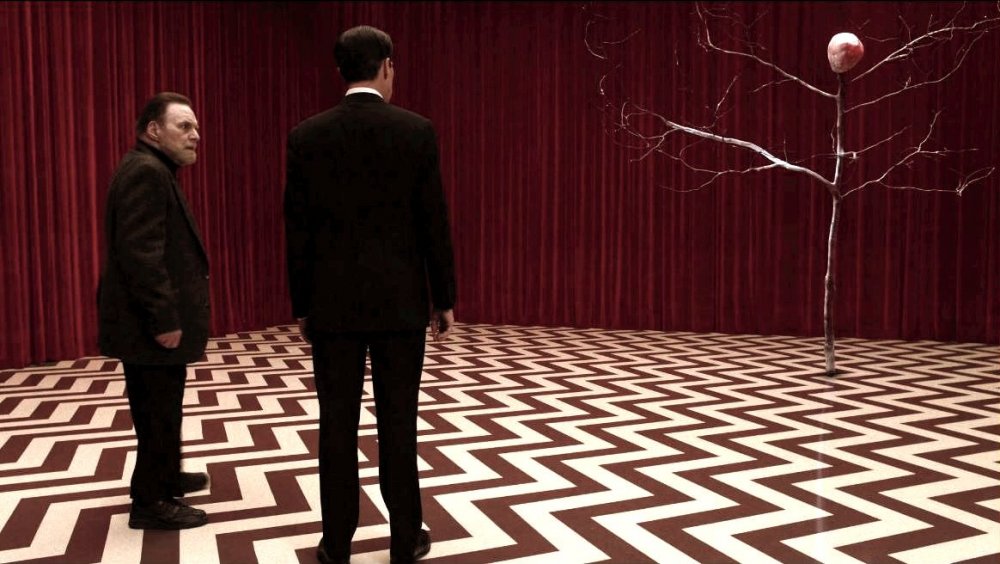

1. Twin Peaks: The Return. 2017. 5 stars. The third season of Twin Peaks may be technically a TV series (it was aired as such on Showtime, one episode per week), but it also ranks on various lists as one of the best films of 2017 (it was screened over the course of three days at New York’s Museum of Modern Art). Lynch himself claimed that The Return is better understood as an 18-hour long film, and it was certainly shot, funded, and edited like a film. Lynch had total control, directing every episode (in seasons one and two, he directed only six of the 30 episodes), and the work stands as a truly singular vision. And for all the experimental innovation of the other two seasons, they ultimately adhered to the formula of a soap opera, with traditional beginnings and ends and cliffhangers that needed resolution in the next episode. The Return is like nothing I will ever see again, and everything Lynch had been building to at this point. The fingerprints of all the mighty works are present: the road trails and character reinventions of Lost Highway, the brutal misogyny of Blue Velvet, the dreamscapes of Mullholland Drive, and a particularly stunning masterpiece episode that feels like Eraserhead in every frame. And yet this isn’t Lynch just repeating himself. Ultimately, The Return is about Dale Cooper’s attempt to rewrite the past and stop Laura Palmer from ever being killed. Whether he succeeds for better or worse (I say it’s for the worse) has been furiously debated, and will continue to be for a long time.

1. Twin Peaks: The Return. 2017. 5 stars. The third season of Twin Peaks may be technically a TV series (it was aired as such on Showtime, one episode per week), but it also ranks on various lists as one of the best films of 2017 (it was screened over the course of three days at New York’s Museum of Modern Art). Lynch himself claimed that The Return is better understood as an 18-hour long film, and it was certainly shot, funded, and edited like a film. Lynch had total control, directing every episode (in seasons one and two, he directed only six of the 30 episodes), and the work stands as a truly singular vision. And for all the experimental innovation of the other two seasons, they ultimately adhered to the formula of a soap opera, with traditional beginnings and ends and cliffhangers that needed resolution in the next episode. The Return is like nothing I will ever see again, and everything Lynch had been building to at this point. The fingerprints of all the mighty works are present: the road trails and character reinventions of Lost Highway, the brutal misogyny of Blue Velvet, the dreamscapes of Mullholland Drive, and a particularly stunning masterpiece episode that feels like Eraserhead in every frame. And yet this isn’t Lynch just repeating himself. Ultimately, The Return is about Dale Cooper’s attempt to rewrite the past and stop Laura Palmer from ever being killed. Whether he succeeds for better or worse (I say it’s for the worse) has been furiously debated, and will continue to be for a long time.

2. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. 1992. 5 stars. This has a bad reputation even among Lynch fans, and I used to have my own reservations when judging it as a Twin Peaks prequel. It helps immensely to get a distance from the first two seasons of the TV series and treat it as a standalone piece, and when you do, a much different film emerges, a horror film above all, and in fact one of the best of all time. The scoring is brilliant, the acting flawless, and it’s by far Lynch’s cruelest film, more so than even Blue Velvet — containing scenes in Laura’s bedroom so terrifying they make parts of The Shining look tame. Fire Walk With Me is about Laura Palmer’s last week on earth, how she has processed years of rape at the hands of her father, and her choice of death rather than allow herself to be possessed by a hideous spirit. This is my second favorite horror film after The Exorcist, and a strong character piece in contrast to the TV series’ focus on mystery and town dynamics. Mark Kermode also thinks it’s Lynch’s #1 masterpiece and makes an excellent case as to why. I’d love to hear what he thinks of The Return, which I think transcends even Fire Walk With Me.

2. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. 1992. 5 stars. This has a bad reputation even among Lynch fans, and I used to have my own reservations when judging it as a Twin Peaks prequel. It helps immensely to get a distance from the first two seasons of the TV series and treat it as a standalone piece, and when you do, a much different film emerges, a horror film above all, and in fact one of the best of all time. The scoring is brilliant, the acting flawless, and it’s by far Lynch’s cruelest film, more so than even Blue Velvet — containing scenes in Laura’s bedroom so terrifying they make parts of The Shining look tame. Fire Walk With Me is about Laura Palmer’s last week on earth, how she has processed years of rape at the hands of her father, and her choice of death rather than allow herself to be possessed by a hideous spirit. This is my second favorite horror film after The Exorcist, and a strong character piece in contrast to the TV series’ focus on mystery and town dynamics. Mark Kermode also thinks it’s Lynch’s #1 masterpiece and makes an excellent case as to why. I’d love to hear what he thinks of The Return, which I think transcends even Fire Walk With Me.

3. Eraserhead. 1977. 5 stars. Stanley Kubrick famously forced his actors on The Shining to watch it. Like the haunted hotel picture, Eraserhead traps you in a dreadful atmosphere where the walls keep closing in. It’s interesting how Kubrick and Lynch tend to work in opposite directions, one’s stories leading to head-trips, the other’s head-trips building to stories if you can make sense of them. I’ve even read that Eraserhead’s tadpole-baby is the antithesis of Space Odyssey’s Star-Child who smiled down on humanity’s technological progress; tadpole-baby rages against humanity, a diseased product of our industrial “progress”. What I still want to know is the Old Testament text which suddenly hit Lynch like an epiphany and cemented his vision for the film; to this day he refuses to come clean about it. My bet is on chapter 3 of Job, perhaps the most existentially spiritual book of the bible, and I can indeed see why Lynch calls Eraserhead his most spiritual film. Not only is it his most profound work, and his most unnerving, it’s also his purest tuning of the dream-consciousness style he’s known for.

4. Mulholland Drive. 2001. 5 stars. IIf Blue Velvet threw me into a new world of cinema I could barely begin to define, Mulholland Drive reinforced the magic 15 years later, at the exact moment Peter Jackson was giving magic a new name. It parades a brilliant understanding of projection in the context of frustrated wish-fulfillment. Diane is the reality, Betty the dream; the first comes last, and makes devastating sense of the second; this reinvented figure is a starry-eyed Hollywood actress who is loved by everyone, especially a woman she lusts for who in real life barely returns her affections. This manner in which people from Diane’s life fill their dream-roles is a brilliant recontextualization of a go-nowhere actress drowning in criminal guilt, and it’s one of the most intimate experiences I get out of any film. I feel like I’m the dual character of Diane/Betty when I watch this, though I have few commonalities with them. The best scene is the lip-synced Llorando, which precipitates the intrusion of reality at the two-thirds point, in the above image.

4. Mulholland Drive. 2001. 5 stars. IIf Blue Velvet threw me into a new world of cinema I could barely begin to define, Mulholland Drive reinforced the magic 15 years later, at the exact moment Peter Jackson was giving magic a new name. It parades a brilliant understanding of projection in the context of frustrated wish-fulfillment. Diane is the reality, Betty the dream; the first comes last, and makes devastating sense of the second; this reinvented figure is a starry-eyed Hollywood actress who is loved by everyone, especially a woman she lusts for who in real life barely returns her affections. This manner in which people from Diane’s life fill their dream-roles is a brilliant recontextualization of a go-nowhere actress drowning in criminal guilt, and it’s one of the most intimate experiences I get out of any film. I feel like I’m the dual character of Diane/Betty when I watch this, though I have few commonalities with them. The best scene is the lip-synced Llorando, which precipitates the intrusion of reality at the two-thirds point, in the above image.

5. Blue Velvet. 1986. 5 stars. This film was my introduction to David Lynch, back when I was transitioning from high school to college, and it was my best friend who actually warned me against it. He loved disturbing movies as much as I, but he sure didn’t like Blue Velvet; in fact he despised it as much as Roger Ebert, whose legendary TV review is still talked about today and contrasts with Entertainment Weekly‘s awarding it the 37th Best Film of all Time. I’m with EW. But what’s fascinating is that this dramatic polarization, which I experienced personally, emerged when it did: the ’80s were the worst decade for American cinema. (Seriously, how many films from 1983-1989 hold up today?) Blue Velvet seemed to oppose the faddish malaise with an insistence on aesthetic that matched its transgressive content. It takes the rot-under-the-small-town theme and injects heavy doses of sadism, sadomasochism, and full-blown lunacy; yes. But around all the suffocating depravity is worked a stunning beauty, particularly in the relationship between the Kyle Maclachlan and Laura Dern characters.

5. Blue Velvet. 1986. 5 stars. This film was my introduction to David Lynch, back when I was transitioning from high school to college, and it was my best friend who actually warned me against it. He loved disturbing movies as much as I, but he sure didn’t like Blue Velvet; in fact he despised it as much as Roger Ebert, whose legendary TV review is still talked about today and contrasts with Entertainment Weekly‘s awarding it the 37th Best Film of all Time. I’m with EW. But what’s fascinating is that this dramatic polarization, which I experienced personally, emerged when it did: the ’80s were the worst decade for American cinema. (Seriously, how many films from 1983-1989 hold up today?) Blue Velvet seemed to oppose the faddish malaise with an insistence on aesthetic that matched its transgressive content. It takes the rot-under-the-small-town theme and injects heavy doses of sadism, sadomasochism, and full-blown lunacy; yes. But around all the suffocating depravity is worked a stunning beauty, particularly in the relationship between the Kyle Maclachlan and Laura Dern characters.

6. Lost Highway. 1997. 4 ½ stars. This one is moderately underrated, but still too much so, and I remember wanting to shoot Siskel and Ebert for giving it two thumbs down. There are shades of the other masterpieces here, especially the small-town suburbia (and underground sexual deviations) of Blue Velvet, and the character reinventions of Mulholland Drive. The best parts are the start and finish, the Bill Pullman parts, showing a jealous man who kills his wife and then resurfaces when his dream-identity breaks down. The German voice-overs to the porno shots are so creepy they’re terrifying — as much as the initial murder, also seen on video. When he comes full circle at the end and rings his own doorbell, announcing what he (and we) heard at the start, the cycle is set in motion again, implying that in his attempt to escape reality, he becomes permanently imprisoned in denial. That’s what the “lost highway” is, and while not exactly a masterpiece, it’s still a work of art.

7. The Elephant Man. 1980. 3 ½ stars. With a moral structure and even sentimental thrust, The Elephant Man isn’t especially recognizable as David Lynch, but it’s a fine piece of work nonetheless. Instead of a surrealist dreamscape, this is practically a documentary. But the subject is gross enough to be out of a nightmare: John Merrick (1862-1890), who was so deformed that his parents rejected him and he became a traveling-circus freak. Also, there is some of Eraserhead to be obliquely found here, most notably in the theme of birth mutation, a horrifying concept that was clearly on Lynch’s mind at this early stage of his career. The Victorian atmosphere with smog and clanging machinery is reminiscent of Henry Spencer’s industrially polluted world. If The Elephant Man waxes melodramatic at points, it also preserves a wonderful ambiguity about Merrick’s caretakers: Bytes’ treatment of Merrick was horrible, but he arguably loved him, if in the way we love our pets. Treves’ humane approach is the one we more approve, but ultimately he’s using Merrick for his own benefit.

8. The Straight Story. 1999. 3 stars. I suspect that Lynch danced with Disney just to show the world he could do G-rated. His family-friendly film is based on the true account of a 73-year old man who drove his, yes, tractor-style lawn mower all the way from Iowa to Wisconsin, in order to visit an ailing brother. Which means it’s a slow-paced odyssey, taking us through rural Midwest towns populated by the sort of endearing characters we see (on the surface, at least) in most of Lynch’s films. We keep waiting for the NC-17 sideshows, but The Straight Story stays out of the netherworld and dwells on tranquility — extended rests between the snail-paced road travel (the lawnmower doesn’t putt over 5 miles/hour), and scenes of vast corn fields. Think Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven, with its beautifully slow camera glides over yellowish landscapes, mix in light doses of small town culture, and you’ve got The Straight Story. It’s a decent film, and a refreshing exercise for a director who usually revels in the dark and sordid, but nothing exceptional.

9. Inland Empire. 2006. 2 stars. If Fire Walk With Me and Lost Highway are underrated gems in the Lynch canon, Inland Empire is the most bloated and overrated. It basically recycles the seedy mystery plots of Blue Velvet and the identity-blurring of Mulholland Drive, but with a sense that Lynch was just throwing darts. He admitted that he wasn’t even working from a script, and it shows: unlike Mulholland Drive which balanced ambiguity and explanation perfectly, Inland Empire traces crazy-8’s non-stop. To those who respond that this is much the point, I call the critic’s competence into question. When all you really have are non-sequiturs and pseudo clues, that’s called spitballing, not artistry. I wanted to like these parallel stories of a “woman in trouble”, not least for Laura Dern’s ferocious performances, both as the actress and the damaged prostitute. And there’s no denying the aesthetic. But Lynch seems to have been intent on simply making the longest feature possible (it’s over three hours) with no substance behind the surrealism we love him for. The result is a kaleidoscope, little more.

10. Dune. 1984. 1 star. This steaming pile of manure by rights belongs at the very bottom, but I’ll cut Lynch a sliver of slack since I think any director would have failed with Dune. (Also, I retain a special hatred for Wild at Heart — but more on that below.) Half the novel is inside people’s heads, and Herbert had such command of inner turmoil that it’s where the story’s true excitement is. Lynch tried his best with internal monologues, but they’re frankly abominable, and no one wants to watch stationary characters process thought for long periods of screen time. On top of this, the characters never come a fraction to life as they do in the book, and events whisk by criminally fast. Dune may not be Lord of the Rings, but it needed more than two hours to do it justice. But as I said, I think it was doomed regardless, which is why even the 4-hour TV mini-series years later was scarcely an improvement.

11. Wild at Heart. 1990. 1 star. Some might accuse me of a jaded perspective, going into my second Lynch film expecting another Blue Velvet. I remember that summer of 1990 too well: it was a late night showing at the crummy Premiere 8 in Nashua, and only two others were in attendance, a woman to the left of me, and a guy all the way down in front as crazy as Dafoe’s Bobby Peru; he laughed like a hyena all the way through, at all the sick parts — hell, he was practically part of the show. But that lunatic made me wonder if that’s exactly what Lynch was doing as he filmed this travesty: laughing at us and just having fun. Wild at Heart is the product of a genius who’s not applying himself. And I’ve revisited it enough times to be confident of my objective distance from that loopy experience at the cinema. The dialogue is a joke (Nicholas Cage’s “this here alligator-jacket is a symbol of my individuality” is exemplary); the transgressive content gratuitous (unlike Blue Velvet’s); the Wizard-of-Oz imagery obtuse. Lynch was out to lunch on this one.

11. Wild at Heart. 1990. 1 star. Some might accuse me of a jaded perspective, going into my second Lynch film expecting another Blue Velvet. I remember that summer of 1990 too well: it was a late night showing at the crummy Premiere 8 in Nashua, and only two others were in attendance, a woman to the left of me, and a guy all the way down in front as crazy as Dafoe’s Bobby Peru; he laughed like a hyena all the way through, at all the sick parts — hell, he was practically part of the show. But that lunatic made me wonder if that’s exactly what Lynch was doing as he filmed this travesty: laughing at us and just having fun. Wild at Heart is the product of a genius who’s not applying himself. And I’ve revisited it enough times to be confident of my objective distance from that loopy experience at the cinema. The dialogue is a joke (Nicholas Cage’s “this here alligator-jacket is a symbol of my individuality” is exemplary); the transgressive content gratuitous (unlike Blue Velvet’s); the Wizard-of-Oz imagery obtuse. Lynch was out to lunch on this one.

(See also Carson Lund’s rankings of Lynch.)

Next month: Ingmar Bergman

Yikes, I've only seen three of these (Blue Velvet, Dune, and Wild at Heart), and the only thing I can remember of Blue Velvet is the music.

Wild at Heart I had totally purged from my memory until now… uh, thanks for that… not.

I sincerely wish I could purge Wild at Heart from memory. Sorry for raising grim shades.

You really should watch Eraserhead and Mulholland Drive if nothing else on this list, perhaps even revisit Blue Velvet. You must have a rather awful impression of Lynch, having seen his two worst films and hardly remembering one of his best.

I've sorta been wanting to see Mulholland Drive for a while. Maybe, “when I have time.”

I think I saw Dune first (dubbed into Italian), then BV in college, and I finally gave up on him with WaH.

I second the fact that watching Mulholland Drive and Eraserhead is an absolute necessity in trying to grasp Lynch. If you don't like those, then and only then can you give up on him.

I've never heard that comparison between tadpole-baby and star-child. You're right that Lynch's creation seems like a manifestation of industrial sludge, but I would disagree that the star-child smiles down on technological progress. The star-child represents the hopeful birth of a new, as-yet-undefined chapter of humanity that transcends the technology that Kubrick is skeptical towards throughout the film.

Your description of Lost Highway kinda made me relive the film. I almost forgot how Lynch uses the doorbell ring as a structuring device, but it's so integral to the film and to the idea that he's denial is a never-ending loop. I remember reading about a psychological disorder called “psychogenic fugue” which is the backbone of the film. It's a process of forgetting the past and assuming a new identity for yourself. Creepy stuff.

I think you've underrated The Straight Story a bit. There's always been a sentimental side to Lynch, as well as a deep affection for American nobodies (see “The Interview Project,” which he produced). I think it's a lot more than just middlebrow Disney fluff. Hell, I can't really see a family sitting down for a Friday night movie and a dinner with this one.

You know where I stand on INLAND EMPIRE, obviously. I'm very fascinated by formal experiments, especially when they reveal so much about their creator.

“When all you really have are non-sequiturs and pseudo clues, that's called spitballing, not artistry.”

I think there's more to the film on a narrative and thematic level than non-sequiturs. Things definitely fit together, just not in a literal, one-to-one manner. And the associative pull is grounded beautifully by a subtle meta commentary on the strange nature of virtual reality in our modern world, the way that we can exist on many different planes at once (TV, internet, social networking, phones, etc.). I see the third act pull back to reveal the crew as a way of adding another mind-boggling layer to the film's dense technological vortex.

I've never heard that comparison between tadpole-baby and star-child. You're right that Lynch's creation seems like a manifestation of industrial sludge, but I would disagree that the star-child smiles down on technological progress. The star-child represents the hopeful birth of a new, as-yet-undefined chapter of humanity that transcends the technology that Kubrick is skeptical towards throughout the film.

Well, I was giving Kubrick the credit of a rare optimism based on the way he changed 2001's ending. He had originally intended to have Star Baby blow up the technology, but went more benign so as not to copy the Dr. Strangelove theme. But you’re interpretation is probably better — certainly one I'd personally prefer, so I'll go with it.

Your description of Lost Highway kinda made me relive the film. I almost forgot how Lynch uses the doorbell ring as a structuring device, but it's so integral to the film and to the idea that he's denial is a never-ending loop. I remember reading about a psychological disorder called “psychogenic fugue” which is the backbone of the film. It's a process of forgetting the past and assuming a new identity for yourself. Creepy stuff.

There are so many moments in this film that uniquely creep me out — the German videos, as I mentioned, the Robert Loggia character, etc. The entire first act could even stand on its own as a powerful short.

I think you've underrated The Straight Story a bit. There's always been a sentimental side to Lynch, as well as a deep affection for American nobodies (see “The Interview Project,” which he produced). I think it's a lot more than just middlebrow Disney fluff. Hell, I can't really see a family sitting down for a Friday night movie and a dinner with this one.

I wasn't trying to imply this is an average Disney film – it's much better, and I've always been hostile to Disney – only that it delivers so much. I was affected by it, and enjoyed it, but I got the sense that Lynch was aiming for something higher like Days of Heaven. I’m not saying it's pretentious; it's authentic, but modest. [Aligning with what you’ve said elsewhere, I've adopted the commandment, “Thou shalt not use the word 'pretentious' in criticizing arthouse film. If the word fits, unpack it another way.”]

You know where I stand on INLAND EMPIRE, obviously. I'm very fascinated by formal experiments, especially when they reveal so much about their creator.

So am I – when they WORK. 🙂

I have a feeling my own top 10 for Lynch is going to piss off or at least confuse both you and Carson.

I'm eager to see it, Jake!